The following is an article from The Annals of Improbable Research.

The following is an article from The Annals of Improbable Research.

A personal insight

by Professor Felicia Schmutzgarten

[EDITOR’S NOTE: The author is a professor at a liberal arts college in the United States. We have disguised her name and location, for reasons that may be apparent to the reader.]

There is a simple way to get girls interested in science. It was revealed, indirectly, at a faculty meeting I attended lastweek.

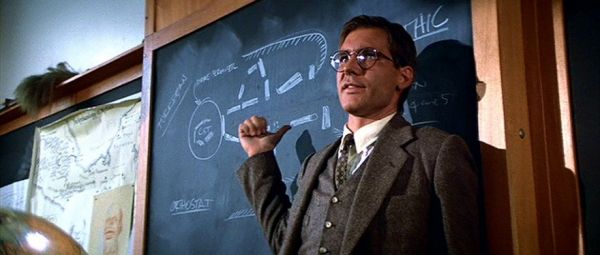

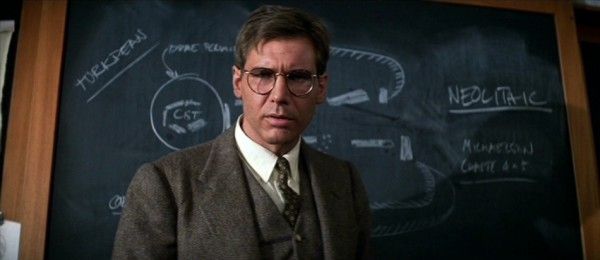

At my college, most of the students are female, and so are most of our faculty members. The problem on the table was student attendance -- or rather, the all-too-frequent lack thereof. “I’m surprised,” said one of our brand-new biology professors, a man I shall call Dr. Fox. Dr. Fox is a recent Ph.D. with Ivy-League medical training, several publications in prestigious journals, a postdoc in genomics, Atlantic-stormy blue eyes, high faceted cheekbones, broad shoulders, and perma-tousled raven-black hair. “Do you know,” he went on in his smoky baritone, “it’s mid-October already and I haven’t had a single absence all semester.”

We all looked at Dr. Fox and he blinked his long, sooty eyelashes at us. Mutters of “Papers to grade ...” “Some calls to make...” “Get my eyebrows waxed ...” were heard as we filed, demoralized, from the room.

But it got me thinking. Thirty years of feminism have gotten more girls into math and science classrooms, but there’s still a long way to go before they catch up with the boys. Most of the overt problems of discrimination, and even the subtler forms of sexism, have long since been swept away: there may be a few Neanderthal throwbacks tucked away in high-school science labs here and there, but overwhelmingly, girls aren’t discouraged from taking advanced physics or jokingly admonished not to faint during the dissection of a cat in biology class anymore. The career advantages of a strong science background are obvious these days, and getting more so all the time. An aspiring journalist is in a much better position if she can write knowledgeably about the genome and split-brain surgery; a potential social worker far more employable if she knows something about neurotransmitters. Yet somehow these persistent cultural messages aren’t sufficient to get female students into their high school and college labs.

A frequently heard remedy is the need for more strong female role models in the sciences; Marie Curie can’t be expected to carry the whole load herself, and posthumously at that. So search committees seek out female science teachers and professors who can provide examples to their students of Women Doing Science, and help to build the female equivalent of the kind of old boys’ network that played such a large role in the success of male scientists like Darwin and Einstein, or something like that.

But after Dr. Fox’s revelation at our faculty meeting last week, I wonder if we shouldn’t rethink our strategy. I am in an almost entirely female social-sciences department. While we have many female students enrolling in our courses, they don’t seem to be taking us as role models in any way: if they did, they would eschew facial piercings, wearing pajamas to class, and the use of the word “goes” to mean “says.” So perhaps the role-model theory is incorrect.

Perhaps what we need to do to get more girls enrolled in -- and faithfully attending -- math and science classes is to hire, not more female teachers, but more entirely adorable male teachers, like our own Dr. Fox.

Because, for whatever it’s worth, I haven’t missed a single faculty meeting since he’s been on staff, either.

_____________________

The article above is from the January-February 2004 issue of the Annals of Improbable Research. You can purchase back issues of the magazine by download, or subscribe to receive future issues. Or get a subscription for someone as a gift!

The article above is from the January-February 2004 issue of the Annals of Improbable Research. You can purchase back issues of the magazine by download, or subscribe to receive future issues. Or get a subscription for someone as a gift!

Visit their website for more research that makes people LAUGH and then THINK.

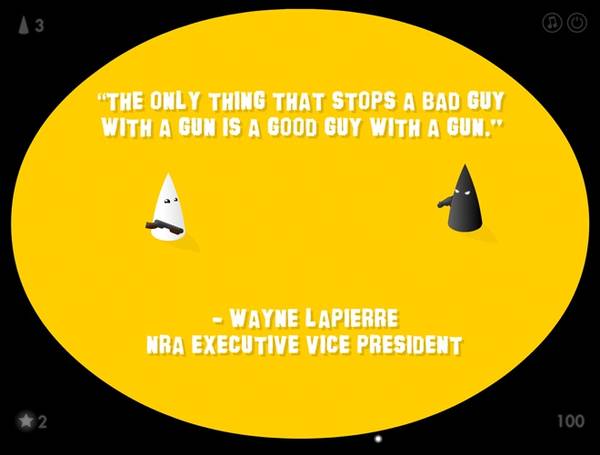

The first level is straightforward. You’re a little white cone-shaped fella, and you need to go get the star before the timer runs out. With each successive level, a new black-colored cone guy is added, and you have to shoot them to get more stars. Sometimes they shoot back at you, or even at each other.

The first level is straightforward. You’re a little white cone-shaped fella, and you need to go get the star before the timer runs out. With each successive level, a new black-colored cone guy is added, and you have to shoot them to get more stars. Sometimes they shoot back at you, or even at each other.

The following is an article from The Annals of Improbable Research.

The following is an article from The Annals of Improbable Research.

The article above is from the

The article above is from the